Have you ever googled a travel guide for your next trip and then wondered why you’re seeing ads for your intended destination as you scroll through your Instagram feed? Instagram and Google are not owned by the same group. How does the social media app know that you’re planning to fly to Spain?

Professor Veelasha Moonsamy has a deep understanding of the invisible traces we leave behind on the web day in, day out – and she knows how advertisers exploit them. Ever since her doctorate, the computer science professor at Ruhr University Bochum has been studying online advertising and highlighting the consequences of hidden data streams – not only for adults, but most importantly for minors.

Cookies track online behavior

“Cookies are the standard technology used to track our online behavior,” explains Moonsamy. They are small files that are stored on our computers and smartphones and log which websites we’ve visited, how long we’ve spent there and what we’ve clicked on. Large advertising marketers such as Google Ads use such data to generate user profiles which they then use to identify our preferences in order to deliver personalized advertising. This can happen on any website, any app and social media – as long as the service sells advertising space. This means that the data doesn’t have to move from one company to another; we simply encounter the marketer in different places on the internet: When we visit a website that runs an ad, the advertiser behind it can plant a cookie on our device and use it to track our activities on that website. They then use this knowledge to show us targeted advertising in other places, for example in a social media app.

“If you’ve allowed cookies on a website, they remain in cache even if you close the browser and open it again days later – unless you delete all cookies manually or configure your web browser to automatically delete them when you close it,” explains Veelasha Moonsamy. This means that information about people’s online behavior remains stored on their devices.

Which ads do kids see on the internet?

In terms of data protection, tracking is a gray area. “It actually involves psychological manipulation, because the online behavior of users is exploited to attract them with targeted advertising,” points out the Bochum-based researcher. Together with colleagues from Radboud University in the Netherlands and KU Leuven in Belgium, she has examined whether ads on websites for children use tracking and which content children are served in the ads.

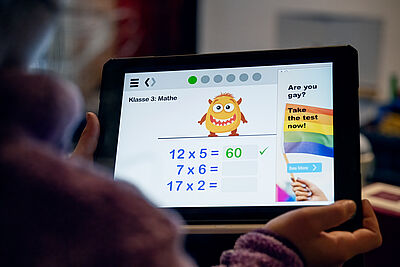

To this end, the researchers created a data set of around 2,000 websites that were specifically aimed at children under the age of 13, as this age limit is crucial in both US and EU regulations; many of these were e-learning platforms. “Creating the data set was a challenge,” recalls Moonsamy. First of all, the team defined criteria that enabled them to filter out websites for children from the vast sea of websites using machine learning. Each website thus identified was then checked by two humans to ensure that it really qualified for the data set.

In the next step, the researchers downloaded the ads from these websites, accumulating approximately 70,000 files in total. This was partly because many pages contained several banner ads and partly because the researchers visited each page several times. “The ads are extremely dynamic, they change every few minutes,” explains Veelasha Moonsamy. “If you reload a page, you’re very likely to see a new ad.”

Seventy-three percent of the ads that were analyzed used tracking. Generally, users only consent to this practice if they accept optional cookies. However, according to Article 8 of the General Data Protection Regulation, children cannot give valid consent; the parent should give consent instead.

Alarming content

Together with her colleagues, she also examined the content of the advertisements that popped up on websites aimed at kids. Not all of them were tailored to the interests of children. “It was a mix of miscellaneous ads, some of them with alarming content,” outlines the computer scientist. The pool that the researchers analyzed contained 1,003 inappropriate ads. Their content ranged from ads for engagement rings and racy underwear to weight loss drugs, dating platforms and tests for homosexuality and depression, as well as sex toys and invitations to chat with women in suggestive clothing and poses.

Laws don't apply

“Technically, laws do exist that regulate which ads children may and may not be exposed to,” stresses Veelasha Moonsamy. “But they are not being complied with.” This is because, from a technical point of view, there’s no difference between websites designed for children and websites designed for adults. As a rule, they’re all fed from the same pool of ads. This is unlikely to change any time soon. Moonsamy explains: “The internet has been around for decades. It’s a complex system that works in a certain way, and we can’t simply implement fundamental changes willy nilly. Doing so could cause the whole thing to collapse.”

As of 17 February 2024, according to the EU Digital Services Act (Article 28), online platforms must not use behavioral advertising when they are aware with reasonable certainty that the recipient of the service is a minor. But who is actually responsible for enforcing the laws that are supposed to protect minors online? The marketer who manages the pool of ads? Or the website provider who rents out parts of their site as advertising space? This remains unclear at present.

Services like a free e-learning platform for children are hardly conceivable without advertising, due to the increasing value in collecting users’ online data. Also, corporations such as Google provide their services free of charge only in exchange for data. “That’s how this ecosystem works,” says Moonsamy. “You get everything for free, but Google gets your data and can use it to make money from advertisers.” If such a practice were to be penalized financially, the advertising business model would collapse.

Protecting children

Veelasha Moonsamy doesn’t believe that the current practice will change in the near future. But: “Ad blockers can help,” she advises. These tools block the content of advertising banners from being displayed. The Bochum-based researcher also recommends that all parents familiarize themselves with the mechanisms behind online advertising and keep an eye on what their children view online so that they can educate them about the dangers.

The next time an ad pops up on your social media that matches your Google search from the previous day, you might remember that nothing on the internet is truly free.

About Veelasha Moonsamy

Veelasha Moonsamy heads the Chair for “Security and privacy of ubiquitous systems” at the Faculty of Computer Science at Ruhr University Bochum and is a member of the Cluster of Excellence CASA – Cyber Security in the Age of Large-Scale Adversaries.

General note: In case of using gender-assigning attributes we include all those who consider themselves in this gender regardless of their own biological sex.