Women continue to be underrepresented in science. However, they can enrich the field of IT security in particular with innovative solutions, new ideas and scientific excellence. About time, on the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, to put the spotlight on the research potential of highly qualified and well-educated women.

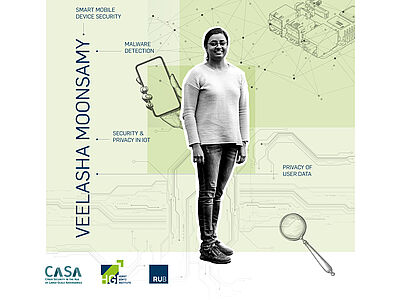

In our Women in IT Security series this year, we present exciting women from IT security at RUB and their very own career paths. One of them is Veelasha Moonsamy, a tenured research faculty at the Horst Görtz Institute for IT Security at RUB and Associated PI in the Cluster of Excellence CASA. In the interview, she talks about her career, her own experiences and gives tips for young female researchers.

You decided to pursue a career in IT. What made you decide to study Computer science, how did you get into it?

For me, it started at school. I grew up in Mauritius. No one in my family had anything to do with IT, I had no one at home or in the media who inspired me to get involved with computer science. I did not experience the typical story you often hear from male peers about how they started tinkering with computers at an early age. Then during high school, which was an all-girls school, I had computer science classes and very good role models - and most importantly, no one to tell me I couldn't do it or that there was no future for me in this field.

I was so fascinated and excited that I then decided to study computer science after high school and chose the IT security study program at Deakin University in Australia. It was a completely new program that was being offered at the time; it had something to do with law and forensics, cryptography and mathematics, all which sounded like an exciting combination. However, when I arrived at the university and entered a lecture hall for the first time, I was completely surprised: there were 200 people in the room and only five of them were women. That's when I started to have doubts. I wondered if I would have a future in this field when seemingly few other women saw the potential to learn computer science. At that time, I contacted the dean (a woman), who recommended me to a female professor. When we met, she reminded me of exactly the right things: why computer science was important to me and why I was there. Then she said, "If the guys can do it, you can do it, and if you want to do it, go for it." The professor later became my PhD advisor.

You've already talked about role models - feel free to tell us more about them: What importance did and do role models have for you?

Role models were an asset for me personally, because they showed me that I can also have a future in the IT field. Having said that, over the years, I also became inspired by role models who were outside of my female academic circles. The first, most important role models for me were my high-school teachers. I wanted to be like them, think like them. However, you cannot take a course on how to find good role models or mentors. My advice to young researchersstu is: Start with yourselves! Ask yourselves what you want to achieve and who you want to be. It is good to get advice from other people, but in the end, it is up to you to create and follow your own path. Role models can also change over time, and I think it is also important to look for role models outside the field of IT as well.

What do you think, to what extent can mentoring programs be helpful for your own scientific career?

In general, I think mentoring programs are good initiatives. However, for me, it's more about knowing when or if you need a mentor. A mentor-mentee relationship is not something that can be forced. At every level of an academic career, there are different challenges. Often you read about the success of others, but it is not immediately obvious what obstacles they had to overcome to get to their achievements. It sounds like things just happened. Sometimes you also have to take matters into your own hands. For example, I didn't know that - until I was told, at some stage in my early career, that you can actually just reach out to people and ask them to be a mentor.

It also takes time to build up a network. Little by little, it comes together like a puzzle. Are there any networks, initiatives or programs that have helped you personally?

My experiences varied from faculties and universities. Some of them offered workshops, special conferences or other career-related programs. During my PhD at Deakin University in Australia, I realized that something had to change: I had been there for five years, but women were still outnumbered in IT. There was a program from the faculty to attract more girls into IT, but not one initiated by students themselves. I pitched my idea to my faculty, and a small initiative turned into an official IT Girls Club. It was just great. We created our own network and shared experiences such as what it was like walking into a lecture hall as a woman and being asked if you were in the wrong place. Our goal was to create a safe space and provide support.

Today, I would advise young researchers, as a first step, to ask colleagues directly about such initiatives, programs and helpful mailing lists as they are probably more up to date on such matters and can provide helpful pointers. It is difficult to keep track and read everything that's available on the Internet in order to keep informed. Keep in mind that building a network takes time. Very often you have to make the first step yourself: Be clear about what you want to achieve. And: Remember that not every piece of advice you receive is always good or helpful for you personally. Different people have different experiences.

Background

The International Day of Women and Girls in Science was adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in 2015. Since then, the UN has been drawing attention to the need for equal participation of women in science, technology and innovation every year on February 11. UN-Women underlines that often structural reasons, such as gender stereotypes or the compatibility of family and science, make it difficult for women to pursue a career in science.

General note: In case of using gender-assigning attributes we include all those who consider themselves in this gender regardless of their own biological sex.

Finding and Following Your Own Path

Copyright: CASA